Is Runna Actually Getting Runners Injured?

Marathon training has always injured people. Apps just give us something to blame.

Over the past week the (online) running community has once again latched onto the idea that Runna, an app that creates personalized training plans, is responsible for an increase in running-related injuries. They think the app’s workouts and AI-adjustments are too intense, the pacing too aggressive, and the progression too fast. When you search for “Runna injuries” you’ll find no shortage of people connecting stress fractures and shin splints to algorithmic training plans.

Is it true? Hard to say. What does exist is a large body of evidence showing that people get injured training for marathons at extremely high rates, regardless of whether they use apps or not. Add to that the a massive influx of new runners and a running culture in flux, and it becomes easy to see why this narrative has taken hold.

A Lot of People Run, and a Lot of People Get Injured

Marathon participation (and running in general) is exploding. In the US alone, there were over 430,000 marathon finishers in 2024, exceeding pre-pandemic levels. Major races are setting participation and application records, and platforms like Strava report double-digit growth in marathon participation year over year. The 2025 London Marathon was the largest mass-participation marathon ever, with more than 56,600 finishers, and over one million applicants for the 2026 race.

But with that growth, across decades of research, different countries, and wildly different runner populations, the conclusion is remarkably consistent: training for a marathon injures a lot of people.

According to one study of runners preparing for the Utrecht Marathon and Half Marathon, nine out of ten participants reported an injury or illness symptom during a 16-week training period. Other research found that roughly 40% of marathon trainees sustain at least one injury, and some studies report yearly injury rates as high as 90%.

A separate study examining New York City Marathon runners found that 48% experienced injuries that impaired training, while about 9% suffered major injuries that prevented them from finishing the race.

These are extremely high injury rates, and they appear largely independent of whether runners use training apps.

Are Training Apps to Blame?

When millions of people are running, and somewhere between 40 and 90 percent of them experience injuries along the way (depending on how they’re measured), you’re going to see a lot of injury stories. As training apps like Runna grow in popularity alongside running itself, seeing correlations becomes unavoidable. Add social media algorithms that reward influencers and their dramatic narratives (and the subsequent responses to them), and every stress fracture starts to feel like evidence of a systemic failure.

But are runners using Runna getting injured at higher rates than runners following a PDF plan they downloaded from the internet? Higher than runners following a training schedule from a book? Higher than runners winging it based on advice from their local running club? Or even higher than runners using a coach? We don’t really know, because no one has studied this in a way that would actually answer the question.

The criticism of Runna rests mostly on anecdotes amplified by social media. Critics tend to point to concerns about ramping up intensity and volume, but there are no comparative studies showing that users of training apps (Runna or otherwise) get injured at consistently higher rates than runners following alternative training methods.

I did find one peer-reviewed study that looked directly at the relationship between running-related technology and injuries. It involved 282 recreational and elite long-distance runners and found that runners who used running-related technology “most of the time” or “always” had higher odds of reporting a running-related injury than those who used it less often.

But, RRT in this context meant almost everything. GPS watches, smartwatches, training apps, and platforms like Strava were all grouped together. If you tracked your runs in any way, you counted as a technology user. The study was cross-sectional, capturing a single point in time, and couldn’t establish causation.

There is likely a simpler explanation. The growth of running brings a growth in new, inexperienced participants. Runners who train more, push harder, and set more ambitious goals (that they may not be ready for) are both more likely to use technology and more likely to get injured. Runners are often being told to “listen to their bodies,” in order to avoid overtraining. But that advice is especially difficult for beginners who have no clear sense of what it actually means, or which signals are genuinely a problem vs manageable.

Interestingly, runners who used their data to modify their training did not show a higher injury risk, which lends credence to the idea that more experienced runners simply had a better idea of what to do with their data to help decrease their liklihood of injury.

That doesn’t mean the critics of apps are wrong. It’s almost certain that some plans push too hard for certain runners. But it’s incredibly hard to tell if it’s demonstrably worse than a bad coach, plan template alternatives or no plan at all.

The Runfluencer Problem

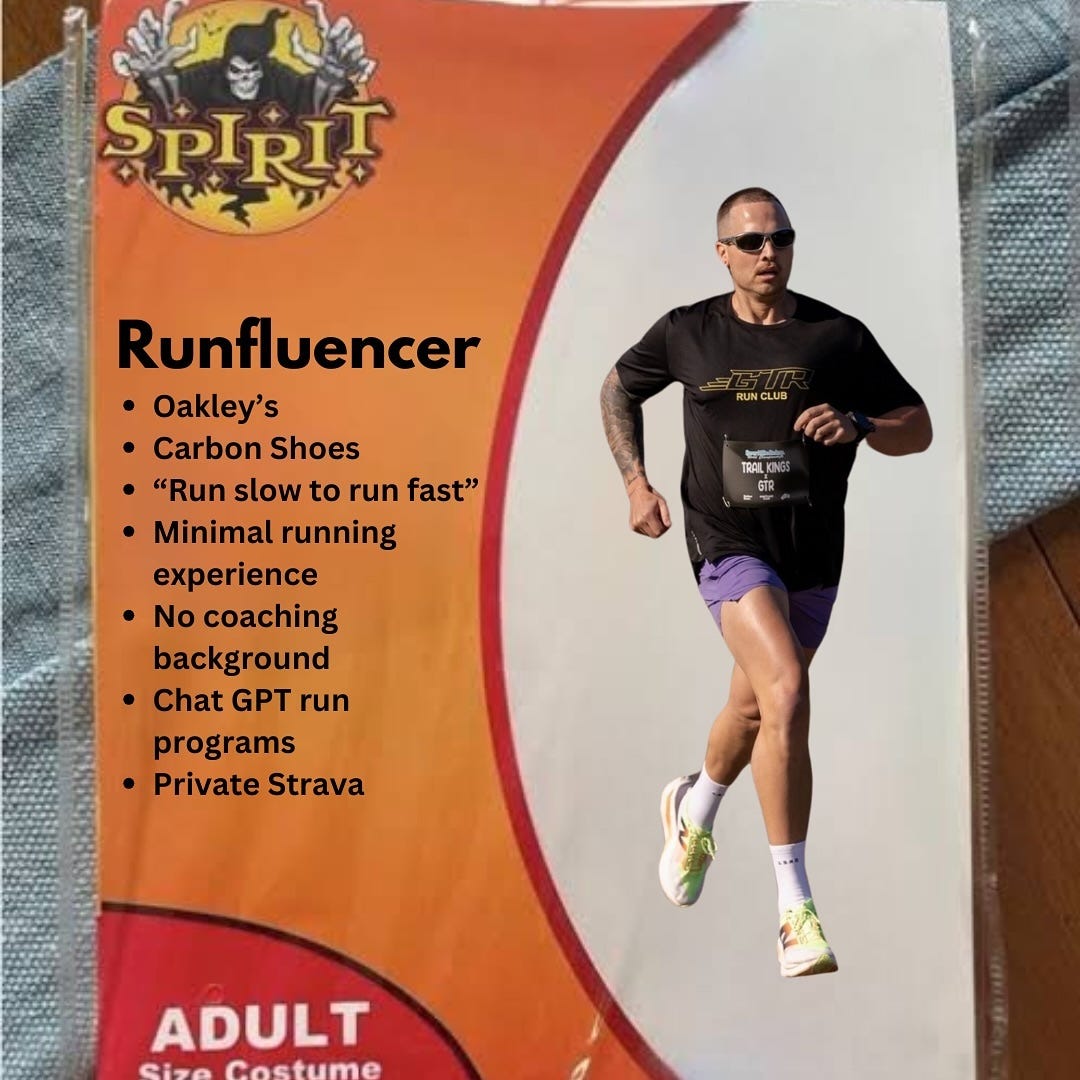

I think negative reactions to Runna are also a response to changes in running culture more broadly. The explosion of running-related content has created a world where platforms are saturated with influencers offering contradictory advice, delivered with absolute, often unearned, confidence. And for many, Runna is associated with that world due to their partnerships with influencers.

Everything must be Zone 2. Strength training is either essential injury prevention or a complete waste of time. You must run fast. You must run slow. High mileage is the answer. Low mileage is the answer. You should be a “hybrid” athlete. You should do these specific exercises. It changes week to week.

This advice comes from people whose credentials range from “ran a fast marathon once” to “took a weekend coaching certification” to “has 50,000 Instagram followers.” The signal-to-noise ratio is absolutely terrible, and the algorithms reliably amplify confidence over accuracy.

Good lord, give me the confidence of a 20 to 30-year-old man who ran a three hour marathon and now speaks in absolutes about training topics that are fundamentally nuanced.

Runna ends up as an easy target because it embodies several things people are already annoyed about: influencers, AI, monetization, and the intrusion of more technology into an activity that is simple at heart.

What AI Might Be Good At

One case against algorithmic training plans rests on the assumption that running is too individual, too context-dependent, too human for an algorithm to handle properly. A good coach, the argument goes, can see patterns that data can’t capture.

The problem is that most runners don’t have access to a great coach who knows them well. Coaching with that level of attention is expensive. For most recreational runners, the real choice is not between Runna and a great coach. It’s between Runna and the time and annoyance of manually modifying a generic plan found online, or training based on fragmented advice absorbed from templates, friends, and social media.

It’s worth pointing out that Runna plans aren’t exactly “AI-generated” in the way that some people might assume. Plans are still designed by humans and professionals, similar to plans you might find online and modify yourself. They use AI to monitor progress and adjust training recommendations based on how you’re performing, but the plans themselves are designed by humans, and likely not too dissimilar from what a coach would prepare.

It’s not better than a coach who knows you, but it’s selling convenience and just enough structure in a more affordable package. Does it adapt as quickly or as effectively? Harder to say.

Pattern recognition across large datasets is actually one of the things AI is pretty good at. In a previous role, I worked on a feature that analyzed thousands of municipal permit comments to identify recurring failures. At scale, LLMs were able to surface patterns that no single reviewer could reliably detect.

In theory, using AI to learn from millions of runners while reviewing one individual’s training could identify early warning signs of overtraining or injury risk that even experienced coaches might miss across large rosters. Runna may not be implementing this particularly well yet, and it is certainly not a panacea. But the idea itself is not obviously misguided.

The Middle Ground

The honest answer is that we don’t know whether Runna is injuring people. I hope someone is working on that particular research. What we do know is that running, especially marathon training, injures a lot of people, and it always has.

Runna feels like a convenient target because it sits at the intersection of several modern anxieties, but helping large numbers of new, inexperienced people train for demanding distances without getting hurt is genuinely difficult. No app, coach, or philosophy has solved that yet.

it's nuts people are quick to blame this running app but not look at the carbon shoes on their feet.

I don't need an app to get injured.