Who's really making money from Rec.gov?

Separating fact from fiction in the debates about fees, accessibility, and public/private partnerships on public lands.

I’ve said in the past that H&T is an intermittent affair, and recently has been no different. After seeing a slew of articles/rants about Rec.gov, I took a deep dive into how it actually works, talked to a bunch of folks, and ended up with one of the longest and most in-depth pieces I’ve written to date. It’s been a while, but hopefully you’ll enjoy this one.

I’ve included a “condensed” version in today’s newsletter (with a summary at the bottom), but the great folks at Field Mag were kind enough to publish the whole thing. I’d love if you gave it a read and shared your thoughts. Onwards.

What is Rec.gov?

Rec.gov is an interagency reservation and booking platform primarily administered by the US Forest Service (USFS) with 13 different agencies involved. Previously operated by Reserve America, Booz Allen Hamilton (a Big 4 consulting firm) took over in 2016 after a lengthy bid and review process that emphasized migration to modern technologies and an agile approach to development. BAH submitted a significantly lower bid than other companies involved in the process.

Was BAH was paid $182 million to build the new site?

The contract was awarded with an incentive-based structure, meaning that BAH took on the risk (and potential reward) of building the platform and continuing to ensure a positive experience for both government agencies and park-goers. A frequently repeated claim is that the government paid $182 million for BAH to build Rec.gov. In reality, the US government paid nothing for BAH to develop and maintain the site, an internal management-focused experience, API, and staff a 24/7 support center. Instead, BAH takes fixed service fees from platform transactions. The oft-cited $182 million was a potential revenue estimate for the 10-year term of the contract using 2015 transaction numbers, fixed fees, and extrapolated growth over the following 10 years.

USFS officials maintain that this choice effectively shifted risk onto BAH and resulted in a successful partnership at no cost to the US taxpayer.

Is BAH making too much money from service fees?

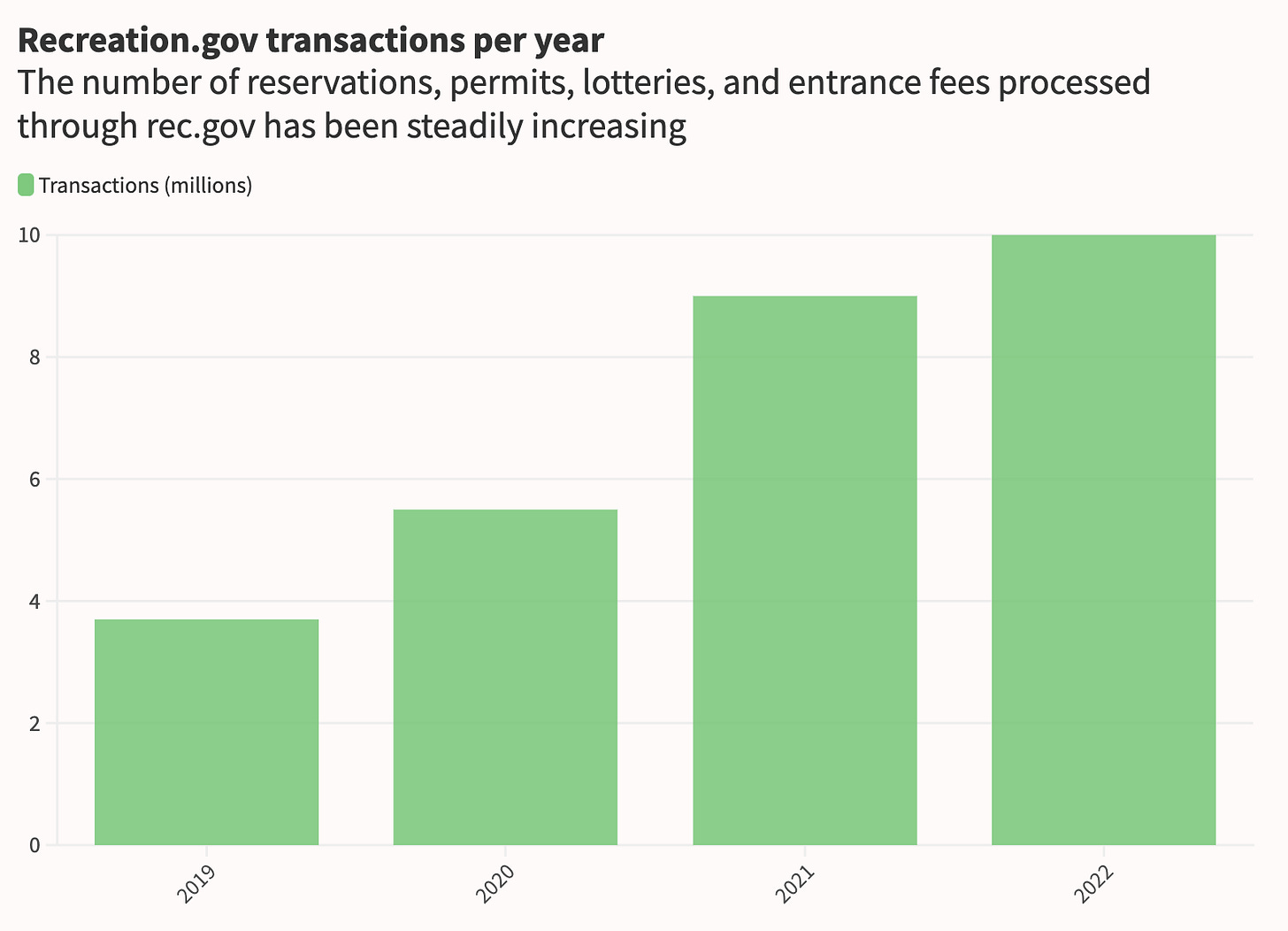

Some point to the fact that BAH is likely to make more than the estimated contract value as a strategy failure. This is primarily due to the rapid growth of recreation visits in recent years as well as changes in recreation patterns due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These factors influenced the introduction of new permits, lotteries, and timed-entry passes in order to control crowds—transactions that often happen on Rec.gov. In hindsight, it certainly seems like an oversight to not have included a “max payout” amount for the duration of the contract.

BAH's increased earnings are due to that increased recreation, as well as new locations choosing to adopt Rec.gov as a technology solution. Rick DeLappe, a program manager for Rec.gov, describes the website as an “enterprise toolset for agencies and land managers to adopt if it serves their needs”—no agency is forced to use it, and neither Rec.gov nor BAH dictate requirements around how to implement it. Individual, local agencies make their own decisions about pricing, types of availability (like the distribution of book ahead vs walk-up campsites), and whether to implement lottery systems.

When I book a campsite, who gets paid?

There are two types of fees on Rec.gov. The recreation fee is the primary charge, typically around $30/night for campsites. Service fees are added by BAH and are $8/reservation for campsites. So, if you book 3 nights at a campsite, $90 goes to the US Treasury, and $8 goes to BAH.

On single night stays, lotteries, and less expensive BLM campsites, the service fee can feel disproportionately high (and this drives many of the strongest complaints).

What about lottery fees?

Despite widely shared assertions to the contrary, the USFS officials I spoke to clarified that only a portion of lottery fees are allocated to BAH. For example, in the Wave lottery ($9), $5 goes to Booz Allen and $4 goes to BLM. Some have issues with the entire concept of paid lotteries for recreation, but unfortunately, reducing the cost or making lottery entries free would likely have the effect of making them significantly harder to win, even if you save ~$8. The cost serves as a minor governor on the number of applications received and generates extra revenue for parks.

Who decides the fees?

The agencies administering permits make decisions about pricing and whether to implement lotteries. BAH does not have the power to change fees, raise fees, or choose to charge new ones; they can only earn fixed amounts per transaction type that were stipulated in the original contract. All payments on Rec.gov go directly to the US Treasury—BAH is then compensated each month based on the terms of their contract and the transaction volume.

For every dollar that BAH earns, many times more goes to various government agencies. In the first four years of the contract, over $1 billion in recreation revenue was generated for participating agencies and facilities, which USFS officials say was reached much faster than expected because of improved technologies, and with the additional benefit of increased efficiency for on-the-ground management and staffing.

Are service fees even legal?

A characterization of the BAH service fees as “junk fees” has led to a class action lawsuit filed in Virginia. A previous 2022 case found that the introduction of a $2 fee in Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area violated the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act (FLREA), which authorizes five major agencies to collect and retain fees from visitors to federal recreation lands and waters. In the Red Rock case, courts found that the BLM did not comply with the public participation requirements for setting fees under FLREA. The new lawsuit cites the Red Rock case, seeks to recover millions of dollars in damages from the service fees charged by BAH, and also alleges that “Booz Allen deceptively runs Recration.gov to create the false impression that the junk fees are paid to the federal land management agencies.”

It will be interesting to watch how this case develops, given that the service fees were established as part of the 2016 contract to pay for operation of the website, and are likely not technically land-use fees and thus may not fall under the jurisdiction of the FLREA.

Should private corporations be profiting off public lands?

BAH and Rec.gov aren’t the only public/private partnerships (PPPs) on public lands. For decades, hospitality services in state and national parks across the country have been managed by companies like Aramark, Delaware North, and Xanterra. Every time someone stays at Yosemite Lodge or grabs lunch at Old Faithful, most of that money is going to a private hospitality partner, not the parks. For example, Aramark pays only a 11.75% franchise fee on gross receipts from hospitality services in Yosemite, meaning that 88.25% stays with the company. Hospitality isn’t the only example—the Statue of Liberty 10-year ferry contract is worth ~$350 million (with a 21% franchise fee).

Just because PPPs are common doesn’t mean that they are good, and it certainly doesn’t mean that the current payment structure for Rec.gov is an equitable distribution of funds based on the amount of work or effort put in by BAH. There’s a case to be made that BAH is making significantly more money than the value it is providing.

However, much like the expertise at the USFS is not in ferry operations or hospitality management, it’s also not a tech company. Some critics suggest that the USFS should have built and operated Rec.gov internally instead of engaging in a partnership with a private company.

This is a surprising view, given that the federal government has a long-standing reputation for outdated, hard to use, buggy, and fragile technology. As recently as 2020, the New Jersey government was desperately searching for developers familiar with COBOL—a 60-year-old programming language. And despite what some may think, Rec.gov is not a simple website. The platform involves integrations between an array of agencies and supports a wide variety of complicated booking options, scheduling parameters, search, and more. As Delappe notes, “Government programs tend to languish over time. We wanted a modern, agile approach and continuous improvement.”

BAH’s involvement is akin to that of a contracted engineering team. That would make the USFS and other agencies the product managers, providing expertise around land and park management, and dictating what new features should be developed or improved by evaluating how the platform is being used by staff and recreation visitors.

What are the benefits of Rec.gov?

While Rec.gov and BAH often receive criticism from consumers, the impact to operations in federal land management has been largely positive (even if opinions of BAH are less than stellar). The original program started with 30 parks and 70 campgrounds. By the fiscal year of 2019, Rec.gov administered 3,680 locations and most recently (fiscal year 2022) counted 5,066 locations on the platform.

Moving processes online has significant benefits for many agencies. Advance reservations and scan-and-pay services significantly reduce the amount of cash that agency employees need to handle in the field and helps staff plan and anticipate visitation. Moving reservation management to Rec.gov is often an operational choice that allows parks staff to spend more time in the field and less time with back-office administrative tasks—a shift that is more important than ever given staffing shortages in recent years.

In Olympic National Park, officials estimated that the previous permit system took park staff approximately 15 minutes per permit to process—for 20,000+ permit applications a year. That’s 5,000 staff hours that are saved every year by moving the process to Rec.gov, and 5,000 hours that staff can focus on the things they’re good at, rather than doing manual data entry in an antiquated system. That’s just one national park, and only the 14th most-visited in 2022.

A former parks service employee described similar situation:

“I used to work in a permit office that handled everything in-house and we were constantly slammed. We only did about 10k a year but that meant a constant line out the door, long waits for visitors, and stressed out employees who didn’t have time to do anything else. Once the guy who maintained the database retired, moving it to Rec.gov was a necessity.”

Glacier National Park recently had a public comment period for a proposed transition to Rec.gov, and explained part of their reasoning:

“Over the last few years, applications for advance wilderness camping permits have tripled. Previously, park staff conducted a lengthy manual lottery to issue advance reservation permits using Pay.gov. Transitioning to Recreation.gov for advance reservations would replace the labor-intensive lottery with a more efficient, user-directed online service.”

In this case, park officials noted that the transition would actually result in lower overall costs for advance reservation applicants, stating:

“These fees represent a slight change from the current fee structure but would result in lower costs for advance reservation applicants. While the $10.00 permit fee to Recreation.gov would be a new charge, a $30.00 advance reservation fee previously charged for all advance reservations via Pay.gov would no longer be in effect.”

Are there trade-offs to making the outdoors more accessible?

There’s no doubt that Rec.gov has made it easier than ever to find recreation areas, reserve campsites, apply for permits, and enter lotteries. The number of new accounts on Rec.gov has continued to grow at a torrid pace, with three million added since 2020 alone. This growth is a major factor in the constant unavailability of popular campsites, the sense of impossibility of winning permits, and drives recurring conversations around whether or not bot accounts are stealing campsites. As I’ve explained previously, there aren’t any bots snatching up reservations, there’s just a lot of people. Officials agree, and maintain that they have a range of systems in place to monitor and prevent this kind of activity and that there is no evidence of widespread, inauthentic reservations.

However, there are legitimate concerns around availability, cancellation practices, fees, and more. There is significant anecdotal evidence that no-shows are a widespread issue; many campers are frustrated that some campgrounds listed as fully booked only end up being partially full on any given day. While there are cancellation fees in place, the policies are clearly not a sufficient deterrent for most people.

The Rec.gov team is aware of the frustrations around cancellations and difficult-to-reserve campsites, and is exploring different approaches to remedy the situation, though they haven't committed to a specific approach just yet.

Different types of advance reservations are already being piloted in several major campgrounds. Both Lower Pines in Yosemite and Mount Rainier National Park have been testing alternative lottery systems, including a pre-lottery that narrows down the number of eligible participants who can book campsites and permits on the day they become available.

It's a challenging balance with regard to guest experience, efficiency, and accessibility. The discourse around Rec.gov is often confusing—many of the same people who advocate for a more accessible outdoors also decry Rec.gov and suggest going back to the “old ways.” Those “old ways” generally involved dozens of disconnected and terrible websites, hard to find information on when or how to get permits, and if you got that far, an opaque mail-in process or spending hours on the phone at the right time. Not exactly an accessible or equitable experience.

How do you make everyone happy?

What does accessibility even mean in the current recreation landscape? Does it mean that everyone should be able to afford to explore the outdoors (keeping fees and prices low, resulting in minimal cancellation consequences) or that everyone who wants to visit a specific place should be able to whenever they want (decreasing permit regulations and resulting in crowded places becoming even more crowded)? If there is this much interest, shouldn’t we build more camping and access infrastructure on public lands (never a popular idea)?

There’s a pervasive sense that Rec.gov and the increase of required permits and lotteries are unfairly restrictive to our right to access public lands. Naturally, BAH is an obvious scapegoat for many of these issues—it’s hard to be a fan of multi-billion dollar consulting companies, and nobody likes fees.

Unfortunately, this is just one of the many complicated issues facing outdoor recreation in 2023. For better or worse, every initiative by a major outdoor brand to get more people outside means more people on the trails, more crowds, more Rec.gov accounts, and increased environmental degradation. This doesn’t mean those campaigns are wrong, it just means that promoting outdoor recreation is complicated. There are already more people who want to recreate in our most treasured places than nature (or USFS staff) can support, and all of us are part of the problem. Outdoor recreation is by nature an extractive activity. Permits, reservations, and lotteries, while occasionally annoying, are necessary measures to prevent overuse and protect these places from irreparable harm.

Many common criticisms of Rec.gov are less associated with BAH, and more related to the complicated, challenging decisions that agency officials have to make about managing public lands. The surge in recreational activities over the past five years led to new strategies to manage visitation, but these approaches often come with significant trade-offs. I’m not a BAH or government bureaucracy apologist. There’s plenty to criticize in this particular relationship, but there’s also a great deal of nuance, and it often feels as if critics are unaware of or unwilling to examine the many trade-offs and consequences of other potential solutions.

The BAH contract technically runs until 2028, although a new phase of requirements gathering for the next contract period will begin years before then. USFS officials acknowledge that there is room for improvement in the current system, and the research and exploration for the next contract will include a thorough evaluation of fee structure, the marketplace pricing model, and more.

TLDR;

Rec.gov is not “owned” by Booz Allen Hamilton. They are basically the tech team that is responsible for the site (and related services).

The USFS paid nothing to build the site, it was built for free and the contract allows BAH to take fixed service fees per transaction type (fees were established in the contract in 2016 and can’t be changed).

BAH does not take 100% of lottery fees

Individual local agencies make the decisions about pricing, scheduling, and lottery requirements, not BAH.

All money transacted goes directly to the US Treasury and then BAH is paid each month based on their fixed fee structure.

There is an important conversation to be had about the fee structure, especially given that the rise in outdoor participation is leading to earnings greater than expected for BAH.

Outdoor recreation in 2023 is insanely complicated. It’s nearly impossible to balance access, crowds, fees, and environmental stewardship in a way that makes everyone happy.

Nice work on this! There are clear benefits to a centralized online registration system, as you rightly point out. But I bristle at the thought that an "incentive-based" structure was an appropriate one for this contract, or that the public needed to avoid the "risk." Did any of the staff you spoke with elaborate on either of these things?

I mean, what exactly was the incentive for BAH? It's not like they are inspiring people to go out and camp. That'd be like saying the DMV is inspiring new car sales because their license plate registration system is oh so fancy. No, you reserve campsites because you want to go camping and need the site to be available to you when you arrive—so you follow whatever instructions allow for that. And it's not like BAH is HipCamp trying to convince people to offer new campsites on their property or something; this is not creating or expanding the market for campsites, it's just taking reservations for campsites that already exist. Right, so is the real "incentive" is getting land managers to adopt your system, because then users will be forced to use your system to make reservations?

Well, it's not even that, because incentive-based structures only work in actual free markets, and that's not the case here. The busiest offices were already using Reserve America, which sucked for many reasons, and they were going to use whatever contract was awarded. And beyond that, the local BLM field office can't just go chose some other vendor to build a reservation website for themselves, no matter how BAH performs. So there's no incentive to beat out a competitor, either. In fact, the BLM office's real incentive is to offload work from their already-overworked office, which saves management headaches and dollars. So BAH doesn't have to win over land managers either, they're being forced to adopt a web reservation system no matter which company won the contract. Again, I'm not seeing an actual incentive here.

I don't buy the line that doing it all on service fees shifted risk to BAH. What risk? Campground reservations are a monopoly on a very popular activity. And land managers and campers were going to use whatever system they were handed—what other option do they have? User fees were as guaranteed to BAH as vehicle registrations are to the DMV. Did it shift the cost from the federal govt, which owns and manages all the campsites being reserved, to the users? Yes, it did absolutely that, no argument there. That’s at the heart of the issue, and often is for these types of contracts.

By pretending that there is a true incentive here, and that there's some scary risk here, BAH shifted all their revenue to a per-registration service fee. Just like a smart financial advisor will charge you a "small percentage fee" on your entire portfolio's value (hey, he only wins if you win, amirite?) instead of a flat fee for their time and advice only when he provides it. Welp, that's the same line BAH used. And if you can do math, you know how that turns out.

So it seems there was not enough consideration placed on the fee schedule and how that plays out. First, it should have been a structured payment for the development of the website, with recurring fees to cover ongoing support costs. Incentive-based doesn't make sense here (what incentive here, exactly, is driving this “continued” development the USFS wants?), and a high per-use premium fee is going to add up very quickly. If you’re going to make the mistake of structuring the compensation as they did, then you absolutely need to add some limits.

Since you’re shifting this expense from the feds to the users, the “max” limit should have protected the users. It should have capped the service fee to a reasonable max % of the recreation fee. To a family, an $8 reservation fee feels far more reasonable for a six-night bucket list trip to Yellowstone where a campsite in a premier destination like that might cost $35/night. It feels entirely different for a weekend camping trip two hours from home at a $10 or $14 USFS or BLM site. An 80% fee for reserving a campsite? Even Ticketmaster would be blushing...

It seems like we’re stuck right now with this contract, but I sure hope that the federal staff coordinating rec.gov aren’t just in defensive posture on this and are really looking at ways to make the next contract work better.