"Don't start an outdoor brand right now"

I discuss the challenging economics facing the outdoor industry with Bill Amos, founder of the recently shuttered brand NW Alpine.

Hi all, thanks for tuning in. My first race in 3 years went well last weekend; I managed to snag 5rd in a 25k trail race (and 2 folks ahead of me accidentally cut the course 😭). Shoutout to Camino Ultra for running a fun event.

Now, looking ahead to what to train for next and also trying to figure out some longer term time in the Alps this winter (If you’ve got suggestions, lmk).

Thanks for reading.

I you have feedback, suggestions, or future collaboration ideas, my inbox is open. Reply to this email or message kyle@hereandthere.club.

If you’re enjoying H&T, please share with a friend or colleague!

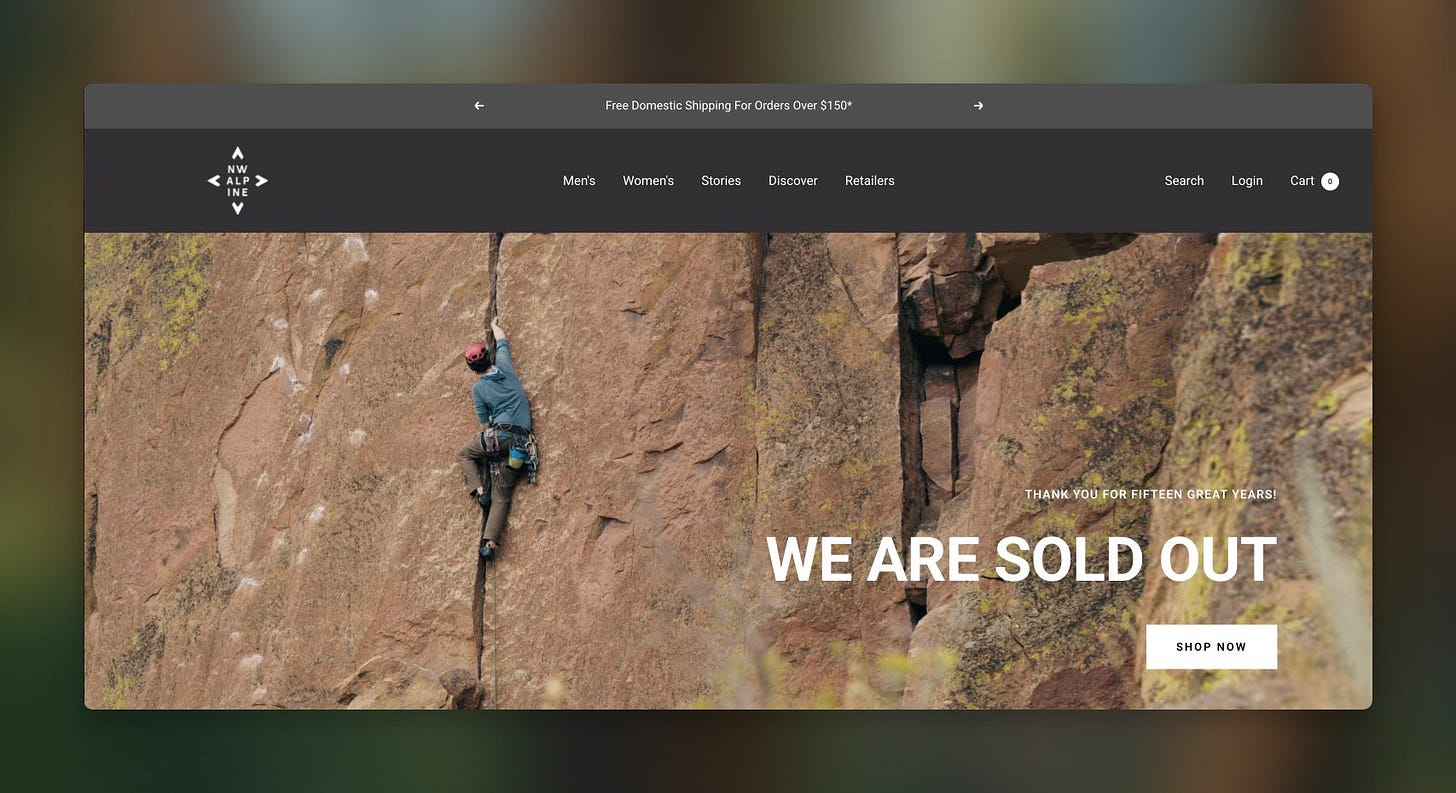

A few weeks ago, Bill Amos announced on LinkedIn that his company, NW Alpine, was closing. After 15 years of making technical alpine apparel in the United States, the company was done. Amos had not just been a proponent of American manufacturing but had built the entire identity of NW Alpine (and his online presence) around it. The decision wasn’t driven by failure in the traditional sense, but by what Amos sees ahead.

NW Alpine’s closure matters not just for what it says about one small brand, but for what it signals about an entire industry facing unprecedented turbulence. I spoke with Amos recently about his background, the challenges brands are up against, and his predictions for what comes next.

A Bit of Background

Amos founded NW Alpine in 2010, starting with 100 pairs of soft shell pants, and grew a small but loyal following of outdoorists who were fans of the American-made approach and high quality technical gear. Seeking more control over production, he later launched Kichatna Apparel Manufacturing, which grew into a 40-person factory in Salem, Oregon, producing gear for NW Alpine and contract clients like Cotopaxi and Fleo.

The pandemic marked a turning point. When hundreds of thousands of dollars in purchase orders were cancelled, the factory pivoted to making PPE. But when Chinese exports resumed, the PPE business evaporated almost overnight, leaving the factory overstaffed and leading to necessary downsizing.

Supply chain disruptions made matters worse. In 2022, REI’s distribution center crisis led a key client to cancel orders for the rest of the year. Amos closed the factory that fall, though it took a long time to fully wind down operations. By the time he turned his attention back to NW Alpine, the outdoor industry was entering what he calls “probably one of the most challenging times in the market.”

A Perfect Storm

As Amos navigated the factory closure, the broader outdoor industry’s pandemic boom had given way to economic headwinds.

The data paints a sobering picture. According to the Outdoor Industry Association, outdoor market retail sales reached $28 billion in 2024, up 1% compared to 2023. But that modest growth masks deeper problems. Casual product categories are driving more sales than technical gear. During the post-pandemic boom, brands overproduced, which then led to a discount cycle with negative impacts across the industry. Casual users tend to buy less and buy on sale. As I wrote for OIA earlier this year, “The post-COVID discount cycle, with prevalent blanket promotions and endless markdowns, has trained customers to wait for the next deal. This undermines specialty retail, devalues premium products, and creates a dangerous dependence on discounting to move inventory.”

Then came tariffs. Trump’s return to office brought sweeping tariff policies affecting the outdoor and manufacturing industries (I wrote about it here). And while there may be a place for targeted tariffs to bolster domestic production, even the most committed domestic manufacturer operates within global supply chains. U.S. manufacturing lost 42,000 jobs from April through August 2025. And even if you wanted to bring some of that manufacturing onshore, “We don’t make sewing machines here,” Amos points out. “Almost everything is imported from China, Japan or Germany, and those all have tariffs on them now.”

The retail closures deepened the trend. Next Adventure, a beloved Portland outdoor gear chain, announced its closure after 28 years. Summit Hut is closing after 55 years. Orvis announced it would close 31 stores and five outlet locations by early 2026, following layoffs representing 8% of its workforce in 2024 and another 50 layoffs citing tariffs in June 2025. Dick’s closed 5 of its 8 Public Lands stores in 2025. And according to Wes Allen, Principal at Sunlight Sports, there’s a rumor that REI plans to close 2 of its flagship retail stores.

Coresight Research estimates that approximately 15,000 stores are expected to close in 2025 across the U.S., driven by “weak consumer demand, inflation, and investor expectations.” While this affected all retail, outdoor specialty stores face unique pressures from casualization and increasing competition from D2C and ecommerce.

The problem with NW Alpine wasn’t execution. By most measures, NW Alpine was doing well. The brand was growing revenue (up 50% YOY) and had eliminated the factory overhead that had nearly sunk the business. But “doing ok” isn’t enough in an industry where the middle market is collapsing.

The Consolidation That’s Coming

The outdoor industry projects confidence publicly. Participation numbers hit record highs. The “$1.3 trillion” economic impact figure gets repeated endlessly on conference stages, in think pieces, and in press releases about the industry’s “power.” But if you start to dig into the financial statements of the major players (or chat off-the-record with a few folks), a different picture emerges.

The dirty secret is that many of the outdoor industry’s most visible players are standing on financial quicksand. And when that ground finally gives way, the question isn’t whether there will be consolidation, layoffs, and closures—it’s who will be left standing to pick up the pieces.

VF Corporation, the behemoth behind The North Face, Vans, Timberland, and Dickies, carried just $642 million in cash against $5.7 billion in total debt as of Q1 FY2026. A debt-to-equity ratio of 4.39 means VF owes more than four times what it’s worth. Debt isn’t inherently a bad thing, and this isn’t untenable, but it’s also not exactly the most stable. VF recently sold both the Supreme brand ($1.5B) and Dickies ($600M) specifically to pay down debt, but remains highly leveraged. This isn’t a company well-positioned to weather a prolonged downturn.

Layoff trends tell the same story across the industry. Patagonia quietly reduced its headcount in 2024. Orvis cut 8% of its workforce in October 2024, another 50 employees in June 2025. REI has gone through several rounds of layoffs and restructuring, scaling back expansion plans from 30 stores annually to just four new locations in 2025.

“Looking at what Patagonia’s done, layoffs and all that, everybody is just financially stressed,” Amos says. “If they’re financially stressed, how are the smaller guys expected to survive?”

Columbia Sportswear, meanwhile, has $579 million in cash and $481 million in debt, a more manageable ratio. While Columbia withdrew its full-year guidance citing “macroeconomic uncertainty stemming from global trade policies,” its balance sheet may provide something its competitors desperately lack: a bit of breathing room. If the predicted negative effects pan out, Columbia has the security to go shopping. The question is whether they plan to use it.

Recent investment crowdfunding by smaller outdoor brands has also revealed uncomfortable truths. Wefunder and similar platforms require public financial disclosures, and the numbers often don’t support the overhead structures these companies have built. “I feel like the value of crowdfunding is getting people that don’t understand the financials well enough to support things because they like it,” Amos observes. “Like, oh, it feels popular in my community, it must grow.” But if you dig into the actual financials, these are not healthy businesses, especially in this market.

The confluence of factors is unprecedented. The inventory glut from pandemic overproduction created a race to the bottom on pricing. Specialty retail is contracting. Casualization means technical brands are fighting for a shrinking pool of committed enthusiasts. Consumers face an average $1,300 in additional tariff costs per household, and the uncertainty that tariff policies has injected into the manufacturing, pricing, and purchasing strategies of both brands and retailers means that some brands are likely to take a (big) hit from betting the wrong way heading into 2026.

“I feel like we’re just like canaries in the coal mine at this point,” Amos says. “When one of the big brands goes down, it’s going to be crazy.”

Can Made in America Still Work?

Despite NW Alpine’s closure, Amos hasn’t abandoned the idea that American manufacturing can succeed in outdoor apparel. “Now is actually a really good time to start an apparel factory because equipment is dirt cheap,” he notes. “I think we could replace our entire factory, probably 100 machines, for $10,000 to $15,000 that we spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on initially. That’s how bad it is.”

But equipment is the easy part. What’s really needed are modern lean manufacturing processes, experienced management (Amos believes only a handful of people in the U.S. could execute), and, most importantly, vertical integration to control margins.

The advantage would be responsiveness. “You could respond to demand, change a purchase order and have that done in like a week, which is unheard of,” Amos explains. “When you’re talking like nine to 12-month lead times from Asia, you’re already a year behind where the consumer is.”

The irony is that companies that could possibly make American manufacturing work are the ones least likely to try it. They’re already successful with their current models, and the risks of bringing production in-house are significant. The companies most motivated to try it (the small brands trying to differentiate themselves) lack the resources and expertise to execute.

What Comes Next

When asked what advice he’d give entrepreneurs eyeing the outdoor apparel market, Amos doesn’t mince words: “Don’t start an outdoor apparel company right now.”

He does clarify–he still thinks there are opportunities ahead for brands, he’s just extremely wary of the next few years and feels that opportunities will lie in whatever comes out of the shakeup, not the immediate future. His decision to close NW Alpine underscores a hard truth about running a business in uncertain times: sometimes the smartest move is recognizing when the game has changed.

“We’re not in a position where we have to close down right now,” he explains. “We’re liquidating that when we still can, when people have money to buy stuff and there isn’t a flood of product coming into the market. If you’re going to panic, panic first.”

It’s a lesson that runs counter to the entrepreneurial mythology of perseverance at all costs. Sometimes quitting while you’re ahead is the right move.

When I asked Amos about his personal goal in winding down the business, his answer was straightforward: “To get out of it, still solvent and not financially ruined at 44.”

By that measure, at least, he succeeded.

Appreciate you writing about this, Kyle. I’d add that no one should start a hard goods company either. There’s a lot that will be lost not just in the industry but in the culture of the outdoors with so many small businesses downsizing or shuttering their doors.

Another intelligent, insightful, and balanced piece. Well done, thank you.